American Hot Wax

by Charles Taylor

It's 1959 and in Floyd Mutrux's film "American Hot Wax" the legendary disc jockey Alan Freed is staging his big rock 'n' roll show at Brooklyn's Paramount Theatre. It will be his last --only Freed doesn't know it yet. In the movie's B melodrama terms, the forces of repression, a/k/a/ the DA's office, suspicious of kids letting loose, and more specifically, of white kids and black kids letting loose together, are closing in for the kill. And Freed goes down fighting, telling them, "You can stop me. But you can never stop rock 'n roll."

The real story isn't so pretty. Driven off the air by the payola scandal, hounded by the government for tax evasion, Freed died, an alcoholic, in 1965 at the age of 43 -- two years more than Tim McIntire, the actor who plays him here, would live to be.

But amid the teeming life of "American Hot Wax" -- an urban pop paradise where neon street life beckons outside the windows of homey living rooms; where hucksters hustle people who turn out to have real talent; where songs that will still sound great nearly 50 years later are tossed off as an afternoon's work; where LaVern Baker's hits come effortlessly and a downer like Connie Francis doesn't stand a chance; where every broadcast Alan Freed makes reaches down into teenage bedrooms like messages from the Resistance; where the boundaries that have defined American life -- keeping black from white, girls from boys, and dreamers from their dreams -- are about to crack wide open -- Freed is a hero. In his hipster's checked sports coats and bow ties, his hair slicked back, one hand keeping rhythm to the records he plays while the other alternates between puffs on a Chesterfield and swigs from the fifth that's his on-air companion, Freed is the snap and jive of the music incarnate. But Tim McIntire brings a big man's sadness to the role. His baby-soft jowls make him look remarkably like the man who has long been rumored to be his father, Orson Welles, and his dark-circled eyes hint at the melancholy that he seems to stave off only for the duration of a three-minute pop song. That's the quandary he shares with his listeners. In "American Hot Wax," the right song at the right moment can wipe away the dross, make the world make sense. But how do you keep that feeling? Freed's sign-off -- "Its not goodbye. It's just goodnight" -- is a plea to his listeners to be strong, to keep the faith. "Could they really take all this away, boss?" asks Freed's driver, Mookie (Jay Leno).

With rock 'n roll a permanent fixture of our culture, pop having even replaced the Muzak that used to play in supermarkets, it may strike some people as quaint to think of rock 'n' roll as any threat to the established order. The squares in the movie who are scandalized by Chuck Berry were comical when the movie was released in 1978. But the movie realized that the fissures opened by rock 'n' roll, the country's second civil war, have never been smoothed over, it says that the freedom and release and pleasure rock 'n roll represents can always be taken away. And by making that pleasure synonymous with the very fabric of life, Mutrux made it seem ineffably precious. At times, the movie invokes the title of a song by Fairport Convention, a band whose versions of English folk music would have been unthinkable as rock 'n' roll in 1959: "Now Be Thankful."

The joy of "American Hot Wax" is that it accomplishes all this with the verve and energy and spontaniety of B movies. Floyd Mutrux, had already shown himself to be a genre whiz with his previous picture, "Aloha, Bobby and Rose," a young-lovers-on-the-lam movie that had real emotional pull and the kind of craft that you can barely find in today's A movies.

Popular art is the art of appropriation and as "American Hot Wax" cuts from one narrative thread to another, as the characters and their talk criss-cross the screen, you think that that this is what Robert Altman might have done if he'd made drive-in movies. Life as well as art is improv here. When a doo-wop group assembled for a recording session is beating the life out of "Come Go With Me" with their funereal version, their producer (played by real-life record producer Richard Perry, whose long face and lantern jaw makes him look like a tough-guy version of the Muppet game-show host Guy Smiley) drags everyone he can find into the studio from the sandwich delivery boy to the janitor ("You look like you got big hands," he tells the guy) to clap and sing along. Then he turns to the lead singer. "OK," he says, thinking fast, "we need something here. Give me a dom, dom, dom, dom . . . dom. Five doms, and a dom-be-doobie." And presto -- doo-wop nirvana.

That scene is about the transformation at the heart of "American Hot Wax." Those three nice clean-cut kids we see practicing close harmony in a stairwell at the Paramount turn out to be the Fleetwoods, whose aching songs may express the purest longing in all of rock 'n' roll. The ditties that Teenage Louise (Larraine Newman in her moment of screen glory as the young Carole King) composes on her family's neglected upright piano turn out to be perfect for the four young black guys who've formed a streetcorner doo-wop quartet (is there any other kind?).

If Mutrux's direction suggests a B-Altman, the screenplay, by John Kaye, suggests another American master: Preston Sturges. Kaye loves, as Sturges did, the glint in the eye that reveals the obsessiveness of "ordinary" Americans, the mixture of wised-up cynicism and open-hearted belief in the patter of everyday speech. Kaye had demonstrated it in his screenplay for the lovely and overlooked road movie "Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins." (And he showed an altogether darker grasp of American myth in his indelible diptych of novels "Stars Screaming" and "The Dead Circus." As portraits of Los Angeles, they can be mentioned in the same breath as Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald.) Everybody in this movie -- the hip folks at least -- are both streetwise and moonstruck. And Kaye's comedy gets a pair of terrific mouthpieces in Jay Leno's Mookie and Fran Drescher's Sheryl, Freed's secretary. Drescher was twenty-one when the movie was made and her grating nasal whine hadn't yet become shtick. Here her voice could stand for the abrasiveness and charm of New York City itself. She's never funnier than when the screeching brakes emanating from her vocal chords are affecting propriety as she fends off another of Mookie's klutzy advances. Leno, with that curling mumblemouth in the midst of his absurdly oversized jaw, like a mini bow lost on a box containing a vast Christmas present looks as if the name Mookie might have been invented for him.

In "American Hot Wax" rock 'n' roll is a pixilated version of democratic pluralism, the only thing that could draw all these disparate people together -- even as it draws lines in the dirt between them and others. But if rock 'n' roll provides a home here for people, like the twelve-year-old president of the Buddy Holly fan club (Moosie Drier, who shines in the movie's most touching scene,) who feel homeless elsewhere, Mutrux and Kaye never let us forget what those folks look like to the movie's arbiters of morality and law. For the DA and his thugs backstage at the Brooklyn Paramount, Chuck Berry, doing the incomparably salacious "Reelin' and Rockin' " is a purveyor of smut. Jerry Lee Lewis, treating the piano as his trampoline, is the most depraved hillbilly. Screaming Jay Hawkins? Jesus! A goddamn cannibal, for crissakes, as Nixon is reported to have said of Idi Amin.

And then there's the guy out front.

Unnoticed by anyone else, a homeless black man sits out in front of the Paramount, oblivious to the excited kids, and then to the marauding cops, intent on banging the cans he's upturned on the sidewalk to use as percussion for his versions of "Lucille" and whatever other tune catches his fancy. What would Freed's teen fans see if they noticed him? Some strange colored guy, providing a little preshow entertainment. What would the movie's defenders of decency see? A tramp, a bum, that nigger in the alley, a phrase Curtis Mayfield had sung in another context a few years earlier. But to Mutrux he looks like the spirit of rock 'n' roll itself, making the noise there always is to be made by anyone who wants to say "I'm here!" A frightened parents' worst nightmare of what will happen to their kids if they listen to rock 'n' roll, he's right out in the open and yet a secret agent. He's the spirit that will sneak its way into crevices and open windows, that will survive Frankie Avalon (or, we hope, John Mayer), a termite artist, in Manny Farber's phrase. When the DA brings down the curtain, he thinks he's won. What that crazy guy in the street knows is that fighting is rounds.

Pismotality writes:

Blogging is generally its own reward, so it was a pleasant surprise to receive a complimentary note from John Kaye, writer of American Hot Wax, about my recent post on the film - gracious of him, too, as it wasn't an unqualified rave.

In fact, if you care to read that post, here, you will see that it's not until around halfway through, in a postscript added after another viewing, that I began to see, or rather to remember, the virtues of a film which, along with its soundtrack, had made a big impact on me thirty or more years ago.

John sent me Charles Taylor's essay about the film and allowed me to reproduce above; I'm glad to see that some of the conclusions I was groping towards in that post were in the ballpark, at least.

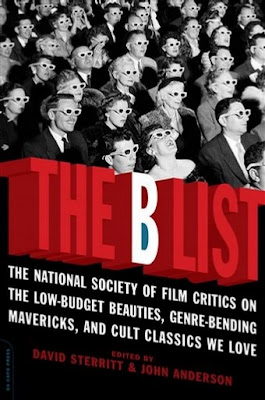

The essay comes from a 2008 book (above) entitled The B-List, about forgotten American films - or to give it the full title it cries out for - The B-List: The National Society of Film Critics on the Low-Budget Beauties, Genre-Bending Mavericks, and Cult Classics We Love.

Edited by David Sterritt and John Anderson and published by Da Capo Press( ISBN: 0306815664), The B-List is currently available cheaply on both the British and American versions of a well-known shopping website should you wish to investigate further. A page on David Sterritt's website, here, includes a link to an NPR interview about the book which you can download for free.

No comments:

Post a Comment