I've already paid tribute to Hubert Gregg but this footnote has become necessary because I've just discovered the details about a record he played on his radio show Thanks for the Memory which had been eluding me for - ohhh, only around the last four decades or so.

Favoured songs were given regular spins on Gregg's nostalgic programme, and he seemed

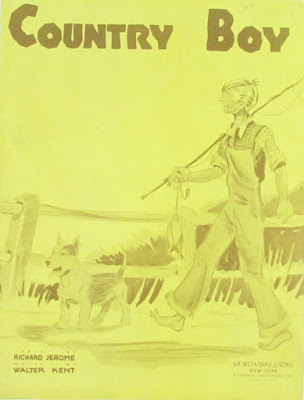

particularly fond of a number called Country Boy, performed by a Hoagy

Carmichael-type singer whose name I had long forgotten. Unlike the lovesick swain of the more famous "gold in the morning sun" lament of that name, however, this subject of this ditty can see no value, metaphorical or otherwise, in his surroundings, hating the picture painted by the narrator of his carefree existence:

You say that it's a pity

You're not back in the city?

Shame on you, country boy!

And that was about as much as I remembered.

I'd searched over the years for some mention of the song online, with no luck - hardly surprising, really, as that same title has been casually bestowed upon any number of compositions.

Today, however, I happened to come across a 1992 edition of Thanks for the Memory and was delighted to discover that the recording I so fondly recalled had been included, and that I could get enough information from the show to allow me to search online for more.Well, there wasn't too much more - or nothing which came readily to hand, anyway - but here's what I have learnt.

Country Boy, with lyrics by Richard Jerome and music by Walter Kent, was recorded in 1938 by Johnny Payne, as Gregg described in that 1992 show - though it seems he hadn't played it for a while by the time of this particular outing:

Some time since, in very late-night imagination, we trotted round to the Elysée Hotel at Madison and 49th in New York to hear Johnny Payne at the piano in the intimate Monkey Bar. He gives four shows, I don't know how, at ten, midnight, two and four - since he's a dream figure to us we can choose. He sits with his back to us at a low upright piano; a feature of his playing is that it sounds as though he's being accompanied by someone else: the music is always several bars ahead of the voice . Having played and sung Love for Sale with enormous success, he's about to give us an encore. The fact that he downed several tots first is in astonishing contrast to the burden of the song ...

Whereupon Hubert played the record once more. It still hasn't made it youtube so I can't embed it below but you can listen to on the Internet Archive website here, direct from a 78.

I note that it was recorded at Liberty Music Shop, which specialised in cabaret and Broadway performers in the days before cast recordings could be found on major labels. It's the B side; the A side is Love For Sale, and as far as I know those were the only two recordings that Johnny Payne made.

Another edition of the sheet music which you can see reproduced up top declares that the song was introduced by Ethel Shutta, though whether in a show or via a recording I can't say; it doesn't seem to feature in the discography of this singer, who first appeared on Broadway in 1922 and would return, many years later, to the very same theatre to sing Broadway Baby in Stephen Sondheim's Follies.

But the song - well, the music, anyway - can be found elsewhere. You can hear it in a 1935 cartoon of the same name, about Peter Rabbit refusing to let the toad Work - schoolwork in his case - squat on his life when he can cramthroat himself, gratis, with all the goodies in a farmer's field. This is, it seems, based on Beatrix Potter's character although I'm guessing it may not have been sanctioned directly by her.

The full details of the plot need not detain us; suffice it to say that the combined catastrophes of a runaway lawnmower and a drenching with maple syrup do little to crush his spirit: in the cartoon's final image Peter is crowing like a cockerel after the syrup has attracted feathers to him - though whether this constitutes a declaration of triumph about a day well-spent or is better understand as a desperate attempt to evade capture and possible punishment I couldn't say.

Either way, during most of his escapades a jolly, jazzy version of Country Boy, sans lyrics, plays. Was it assumed that the audience would automatically make the connection? Was Ethel Shutta's performance, in whatever medium, well-known by the time of the cartoon's release in cinemas? Neither lyricist nor composer are mentioned, however: the musical score is solely credited to Norman Spencer.

Richard Jerome was otherwise known as Jerome Jerome, though his real name was Jerome Bernstein, according to this page on the SecondHandSongs website, which lists four compositions cowritten with Walter Kent, covered by a fair number of jazz or "sweet" orchestras. Eddy Duchin's recording of Love Is Like a Cigarette, with vocal by Peter Woolery, can be heard here.

The other side of Johnny Payne's record, Cole Porter's Love for Sale, can also be heard on the Internet Archive here.

Walter Kent had more than one collaborator, and his page on the site, here, lists twelve compositions including The White Cliffs of Dover (lyrics by Nat Burton).

Sadly, there are no lengthy articles about those involved in Country Boy to quote from here - or if there are, I haven't found 'em. But I did come across an interesting snippet by a possibly interested party in the November 1934 edition of an American magazine called Radioland.

In what appears to be a regular column, Rudy Vallee's Music Notebook, the crooner offers his assessment of a number of new songs, considering Country Boy to be:

[Publisher] Witmark's attempt to find another Lazy Bones or Puddin' Head Jones. By Richard Jerome and Walter Kent, who I feel, while producing an excellent song, have brushed very closely the wings of the muse, as did Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer when they wrote Lazy Bones.

Which, despite that fancy phrasing, appears to be an accusation: that Puddin' Head Jones came first and the other two are merely attempts to write in the same style. As far as I can tell Lazy Bones was actually published a few months before Puddin' Head Jones, though it may well be that the latter was performed in public or broadcast on the radio first. That said, Vallee himself recorded Puddin' Head Jones, which might explain his wish to assert its primacy.

According to the SecondHandSongs website the first recording of Puddin' Head Jones, written by Al Bryan and Lou Handman, was by Fran Frey and His Orchestra in October 1933; Vallee's rendition was a couple of months later.

But Lazy Bones is not a carbon copy of Puddin' Head Jones. The lyrics of the latter song, wholly unknown to me before reading Valleee's column, do not endorse or excuse lassitude in the same way as Mercer does in Lazy Bones: the moral of Jones's story seems to boil down to: "Don't think too much, be a happy idiot because things will magically come good for you anyway."

Like Lazy Bones, which was a big hit in the depression, selling when other numbers weren't, presumably this also caught the popular imagination, even if it hasn't endured in quite the same way. Puddin' Head Jones is the tale of a supposed dunce who makes good: he "couldn't spell Constantinople, / Didn't know beans from bones", but there is a happy outcome to the extra lessons his mother asks for:

All of the kids to the teacher carried

Candy and ice cream cones

But who do you think the teacher married?

Woodenhead, Puddin' Head Jones!

That's the image chosen to adorn the sheet music, shown here in an edition associated with Ozzie Nelson, bandleader father of Ricky ...don't know about you but I reckon Jones actually looks a bit of a brainbox here, what with the glasses and everything:

After their unlikely conjoining Puddin' Head sticks to a job and to his earnings with equal fervour, as demonstrated with a simile such as might be associated with a country boy:

Money stuck to him as close as corn upon the cob

He never spent it in a cabaret

Which leads to another (for him) happy result:

Stock market crashed, then came depressionIt's interesting to compare those first two recordings: the original is sprightly but Vallee's delivery has been slowed to a pace which suggests a dullness of wit .. and might put the modern listener in mind of .. well, Lazy Bones as it is usually performed. Was that part of Vallee's beef about Mercer and Carmichael?

Bankers cut down their loans;

But who do you think had all the money?

Woodenhead, Puddin' Head -

Woodenhead, Puddin' Head Jones!

According to Philip Furia's book America's Songs Lazy Bones took quite some time to come into being from the moment Mercer declared to Hoagy Carmichael that he wanted to write a song of that name:

That first day, they worked out the first sixteen bars, a month later they got the bridge, and three months after that, they got the ending.

The delay was, it seems, because of Mercer struggling to come up with the appropriate lyrics but

Soon Lazy Bones was selling fifteen thousand copies a day, perhaps because something about its languid melody and colloquial lyric touched a chord during the Depression.

It's also interesting to note that the line "You never hear a word I say" was the composer's, as cheerfully admitted by Mercer: "I got credit for it because my name was on the lyric."

It might seem a long time to assemble a short set of words, but some readers will recall that Hal David supposedly took a year to find the right word for a line in What the World Needs Now Is Love: would "Lord, we don't need another car park" or some such still be sung today?

Three songs, then, all written around the same time, only one of which has endured.

Why? Well, Puddin' Head Jones is so specifically about the Depression, and moreover such a tall tale, that it's not hard to understand why it is beached in its time. The Lazy Bones character may be, as Philip Furia, suggests, "blissfully unaware of the terrible need to work", which is certainly something which would have had an additional significance at a time of mass unemployment, but there is nothing specific in the lyric to anchor it to the thirties in the same way.

But what about Country Boy? Listening again to Johnny Payne's recording, his performance is utterly charming ... but if we put that aside and coldly compare Richard Jerome's lyric with that of Johnny Mercer's for Lazy Bones it's Mercer (with that additional contribution by Carmichael) who seems far more nuanced: Jerome relies on cliches of the "shady nook/babbling brook" variety to summon up bucolic life - plus it's essentially it's a one-joke song.

Here's Carmichael's 1933 recording of Lazy Bones with a brief commentary by him at the end:

And here is some sheet music from 1933 which shows that Ethel Shutta was associated with this song as well as Country Boy:

Did its superior qualities mean that Shutta subsequently dropped Country Boy?

Perhaps if Johnny Payne had recorded more then a greater number of people would be aware of the number on compilations; as it is, I'm not sure whether there were any recordings by this artist other than this two-sided disc.

Which raises a few questions. How long was his residency at the Elysée? Did a regular supply of those tots which Hubert Gregg saw lined up for him in the Monkey Bar do for him in the end?

I don't know; I only know that that song, and Johnny Payne's performance, has haunted since the 1980s and I'd never heard it played on the radio again after Hubert Gregg's death. So it's pleasing to think that now I can summon it up whenever I want - and, indeed, to hear the voice of Hubert Gregg once again, guide to so much wonderful music.

Links:

Tribute to Hubert Gregg here.

Review of his autobiography, Maybe It's Because ... here.

This post was updated 24/3/22.

No comments:

Post a Comment