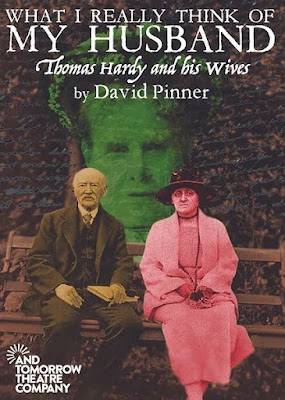

My recommendation comes rather late, but if you are based in London and interested in the relationship between Thomas Hardy and his wives I can recommend the play What I Think of My Husband by David Pinner, running at the Grey Goose Theatre in Camberwell until Saturday, 2nd December.

You can find fuller details at the theatre's website (link at end), but for those who are unfamiliar with the story the essential facts are that the writer Thomas Hardy's marriage to his first wife Emma soured over time, with the couple eventually living largely separate lives under the same roof, but an outpouring of grief and guilt after Emma's death led to a sequence entitled Poems of 1912-13, generally agreed to be his best work in that form.

The play contrasts the interactions of the elderly couple with fleeting glimpses of the young lovers they once were and also details the progress of Hardy's attraction to the younger Florence Dugdale, who is installed in Max Gate, the Hardys' home, as his secretary then becomes his second wife after Emma's death ... only to find that the bargain she has struck isn't all that she imagined.

During the first act the play unfolds in fragmentary scenes which show us, among other things, how wilfully awkward Emma could be in social situations (though Edmund [Gosse?] seems to take matters in his stride) and how ill-matched she and Hardy have become over the years, for all that early passion.

But considerable sympathy is shown for her plight too, trapped as she is in a situation so far removed from her early expectations. As played by Laura Fitzpatrick Emma is alternately exasperating and beguiling, which is, I think, as it should be. As I wrote in an earlier review of a radio play about Hardy and his second wife, there is an element of sitcom about this relationship, and just as Harold Steptoe's sense of being trapped with his father gives him license to be verbally abusive to his captor so the equally impotent Emma's jibes make perfect sense: she can mock and attack the character of the women he flirts with as viciously as she likes precisely because she is fully aware that she is incapable of effecting any change his behaviour.

But sitcoms depend on the cycle never being broken, and equilibrium safely restored at the end of the episode. Florence is no mere flirtation and is soon installed in Max Gate as Hardy's secretary - even seen by the unwitting Emma as an ally in the scene shown at the top of this piece in which she uses Florence's position to gain access to the writer's sanctum sanctorum while he is out and gleefully chucks all his papers in the air while the new employee frantically struggles to put them back in order.

The above happens in the second act, which takes things up a notch: having set out the situation through the snapshots of the first half the painful reality of Emma's lot and the sheer sadness that this form of prison represents for both sides of the partnership gradually become more poignant as we move towards the inevitable end. We see Emma becoming increasingly frail and then dying, followed by Florence's agreement to become Hardy's second wife, only to be followed in turn by an ironic coda.

Despite the second Mrs Hardy redecorating the gloomy Max Gate - neatly suggested in the minimal set by the simple placing of a tablecloth - there is no escaping the spectral presence of the first Mrs Hardy as "T.H." becomes increasingly immersed in thoughts of Emma as she once was, processing his grief via a series of poems. (It's not quoted in the play, but in Hardy's biography, credited to Florence though largely written by Hardy himself, we are told that Hardy was "in flower" when he wrote those tributes to Emma's memory. His phrase or hers, I wonder?)

Playwright David Pinner weaves extracts, sometimes only a few lines, from Poems of 1912-13 and other works, such as "I look into my glass", into the play, both at the end and earlier in the action; this made me hungry to hear some of the originals again in full but it was probably the right decision: a complete poem is a story in itself, and what we're watching is what led to the poetry.

It also seems a wise decision to have the young lovers figuring only intermittently: flashes of memory which only become substantial as Hardy revisits their relationship - literally, through journeys to the places they knew, as well as through his compulsive writing of poems - after her death. Aliya Silverstone and Andrew Crouch, the actors playing the younger version of the couple, double efficiently as servants at Max Gate, the Hardys' home, and anyone else required, which accords with the pleasing minimalism of the set and props: in addition to the single tablecloth mentioned earlier we see, for example, empty picture frames for our imagination to populate - and in this play, to paraphrase the familiar warning at this time of year, a wreath is not just for Christmas.

Edmund Dehn, who plays Hardy, has something of the hangdog expression familiar from photographs and paintings of the writer in his later years, and conveys the convincingly the air of a long-suffering spouse - even if he is the one who has contributed to that suffering. And that patience is enough to suggest the love which once burnt more brightly. There is even a touching moment when the pair frankly admit to each other that the love, or the fiery excitement and happiness associated with it, has gone - and whether or not that derives directly from Hardy's or others' writings (I don't know) that mutual acknowledgement feels right.

But nothing gets in the way of his writing, as Florence (Isabella Inchbald) discovers at the play's end, her enthusiasm about becoming the woman behind a great man replaced by something more like resigned acceptance: she had once inspired his poetry but now her predecessor is his sole subject.

I can add an anecdote, not from the play, which encapsulates the fate of the second Mrs Hardy. It comes from R.C. Sherriff's highly entertaining autobiography No Leading Lady. When the play Journey's End brought Sherriff acclaim in the late 1920s he got to meet some of the great literary figures of his day, including J.M. Barrie (a hilarious, absurd encounter which you will have to read for yourself) and Hardy and Wife.

I don't have the book to hand but remember the gist of a remark Florence made to Sherriff when they were alone, or at least not within hearing distance of her husband. She complained to him that the day before she had been obliged to wait patiently in the cold and gloom as her husband stood for an hour (or however long) in a muddy field, all because it had some sort of distant association with Emma - a typical outing for the couple, one suspects.

What I Really Think of My Husband (the title is taken from a piece of writing by Emma Hardy) is running at the Golden Goose Theatre at 7.30pm until Saturday December 2nd. It's a short walk from Oval tube and around a ten minute bus ride from Vauxhall (in one direction) or Peckham (in the other) on the 36 or 436.

The Golden Goose website, with full details of how to book, can be found here.

Grimful Glee Club, my review of a radio play about Hardy and his second wife, is here.

The play has inspired me to look at the best of those poems again, which

I'll do in a later post rather than delay the posting of this

time-sensitive - take that how you will - piece.

No comments:

Post a Comment